On the Extreme Swings in Game Building Design

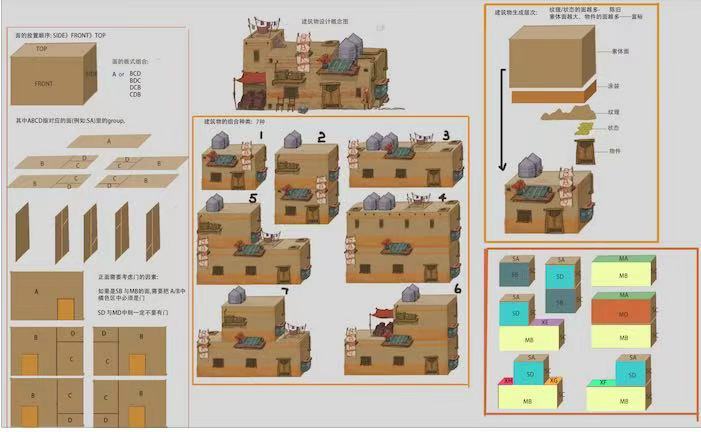

The Early “Gameplay-Only” Extreme

In the early stages of designing buildings for the game, I started entirely from a “gameplay-first” perspective, obsessed with arranging blocks and color patches. Back then, I almost completely ignored visual aesthetics, focusing solely on symbolic representation: as long as the exterior wall color matched, players could instantly tell whether it was a “shop,” “house,” or “warehouse.” Structural styles or regional differences? Not considered at all. This approach might barely work in a single small town scene, but once scaled to an entire planet with diverse terrains, it felt painfully thin and inadequate.

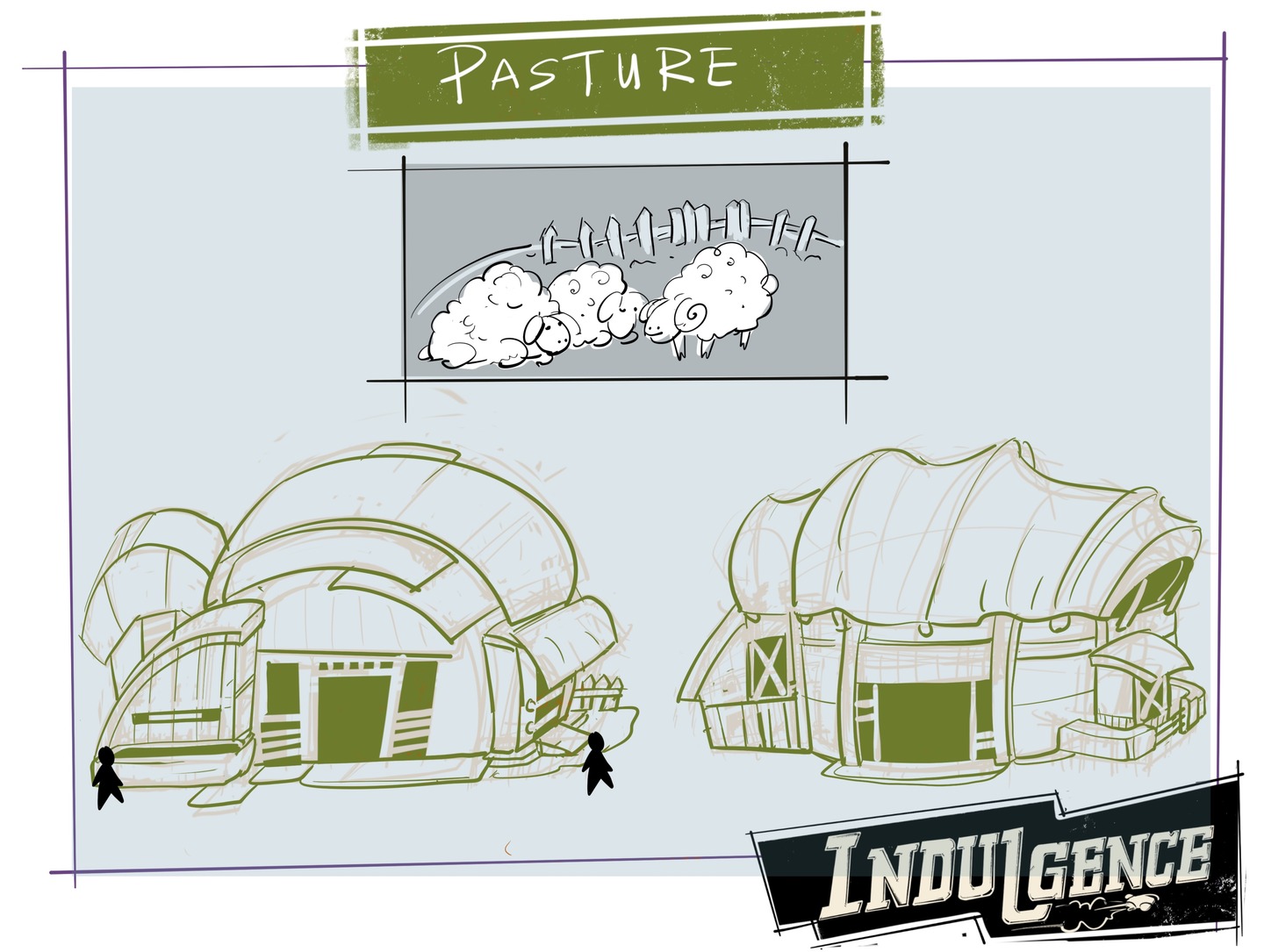

Jumping to the “Pure Freedom” Extreme

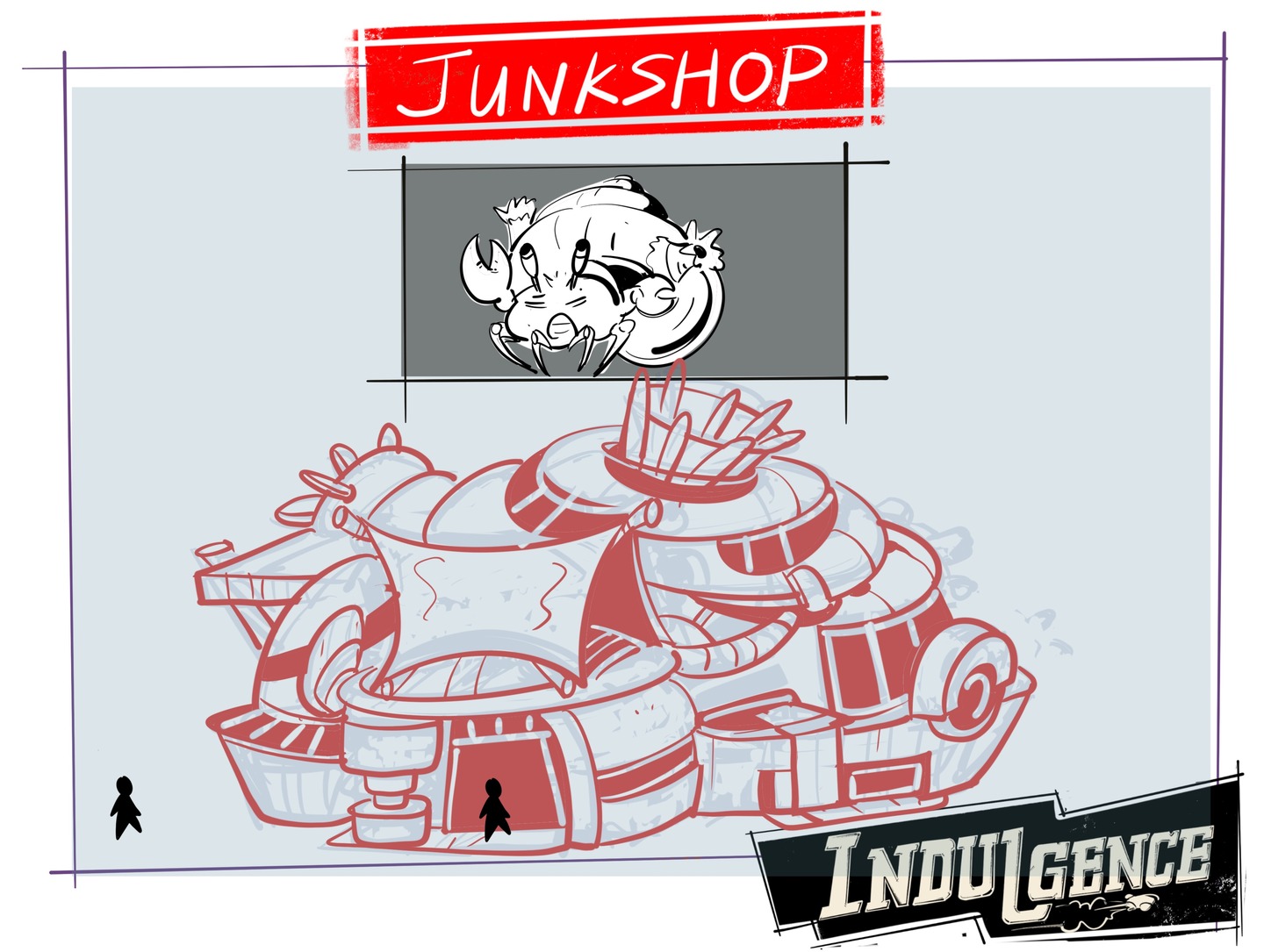

After being driven half-mad countless times by my own “block puzzles,” I decided to let go completely—this time abandoning even the arrangement rules and chasing only “feeling” and silhouette impact. During that period, I mapped each functional building to an animal and directly mimicked their forms in a cartoonish way, producing a huge pile of wildly imaginative line drawings. From one rigid extreme, I dove headfirst into another extreme of total freedom.

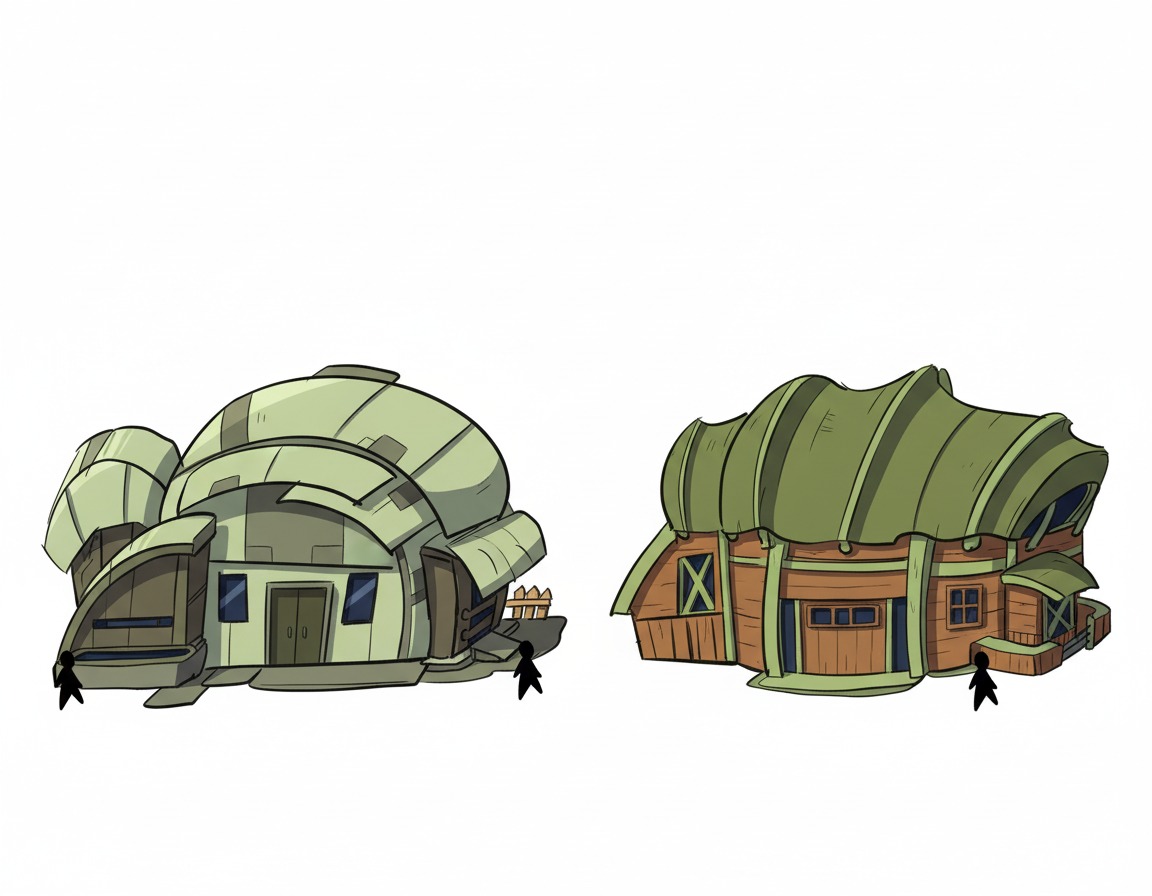

The Hybrid Compromise: Fixed Silhouette, Variable Skin

Once the line drawings were finalized, my plan was: strictly follow the silhouettes, but vary colors and materials based on the local terrain. For example, the same “inn” could be wooden in a forest and brick-and-stone on the plains. This kept strong, consistent visual recognition while allowing the building to interact with its environment.

Clear Pros and Brutal Cons

The advantages were obvious: extremely high functional recognition—players could identify a building at a glance even on a massive map. But the drawbacks were equally fatal: almost zero interchangeability between buildings; each one was far too unique. For the designer, this style was the most controllable and allowed the greatest personal expression, but for gameplay and narrative, it felt overly rigid and lacked flexibility and surprise.

Not Adopted, Yet Deeply Rewarding

In the end, this version was not adopted as the final scheme. Honestly, though, the “animal mimicry” phase gave me the greatest sense of achievement in the entire design process—because the freedom was absolute, I could temporarily ignore size, details, modularity, and all constraints, and simply shape houses that felt truly “alive” according to my imagination.

The Eternal Tug-of-War

Game narrative and visual expression are always a pair that requires constant tug-of-war balancing, especially in original indie development with no prior games to reference—everything has to be figured out from scratch. It tests not only pure visual expression ability, but also how to find a landing point among gameplay needs, narrative demands, and project resource limits. The process is painful with endless compromises, yet precisely because of that, it sparks the most primal and precious creative power in design.